Last updated on December 15, 2023

by Mike Ricketts

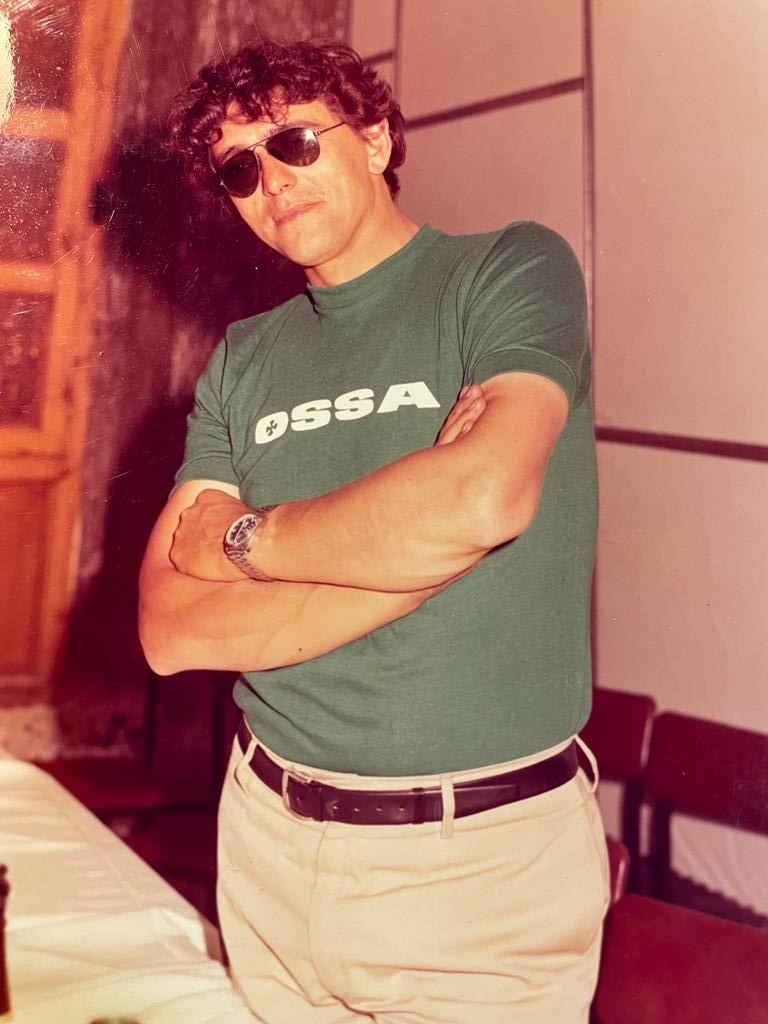

For the third and final part of this article, we move to Salamanca in Spain. Manuel Iglesias Pampliega (Manolo Cachorro to all that knew him) was born in Salamanca in 1936. From an early age, Manolo was obsessed by motorcycles – any motorcycles.

Manolo Cachorro grew up to be a very talented, self-taught mechanic/engineer, eventually opening his own small workshop. Growing up at a time in Spain when the motorcycle was the primary means of transport for the majority, Manolo was always in demand. He was an astute businessman, and it is said that he always kept 2 Hispano Villiers engines in a state of readiness in his workshop, so that he could make an immediate exchange to keep the customer mobile, then repairing the customers engine as and when he could.

Between 1957 and 1965, Manolo was one of a group of young riders competing in regional road race events – it was quite common then for local towns to arrange an urban circuit for racing.

A talented rider, Manolo was virtually a semi-professional rider for Bultaco during these years. Urban Grand Prix circuits have virtually all disappeared now, but one does still exist – the Gran Premio de La Bañeza (a small town about 170 kms North of Salamanca). Joining Manolo in his “La Charra” group of riders were Carlos Hernández López, José Hernández Monago and Julián Molina, who together formed an extraordinary group of riders. In 1964, Julian Molina competing at the urban circuit of Avila, collided with a wall and died from his injuries. This was a turning point for Manolo Cachorro and his fellow surviving racers, and they retired from competition. The death of Molina had hit Manolo hard, but his love of motorcycles continued, and he started to prepare bikes for others to compete with.

Manolo had years of experience in preparing single cylinder motorcycles for competition and some of his exploits had appeared in the motorcycle press of the day. These preparations helped to secure his reputation as a skilled and innovative engineer and a spell as the Competitions Manager for Avello Puch. One of these was his Ducati 75 for which he designed and built a rotary valve induction system.

In later years, Manolo would go on to create a water-cooled OSSA 230cc that he had fitted with his own reed valve induction system but, for this article, we are concentrating on what he did with the OSSA Yankee 500.

As said earlier, Eduardo Giro had wanted to create a Spanish Sports bike beyond anything else available at that time in Spain. An OSSA Yankee 500 in race trim was tested at the Monza circuit. The Motorcycle Press of the day said that it was producing 68 HP and Phil Read took it through the speed timing device at an impressive 273 km/h. This is even more impressive when compared to Agostini achieving only 278 km/h on the full factory supported MV3. The OSSA Yankee 500 was eventually put on the market in 1976 but it proved to be a problematic bike – fast with impressive performance but it suffered badly from defects. The earliest clutches failed very quickly, and the connecting rods broke with regularity.

By 1977, Manolo Cachorro had an OSSA dealership in Salamanca, and he saw at first hand the problems that OSSA Yankee 500 owners experienced and the damaging effect it was having on his business, as the OSSA brand reputation suffered. For Manolo, improving the OSSA Yankee 500 became a temptation that he just couldn’t resist.

When enthusiasts try and improve the performance of a bike for the track, they try various things, depending on their skills and budget. Whilst some will try and reduce weight by changing cycle parts to lighter alloy fittings (footrests etc), others will drill holes in casings and brackets etc to create more weight reduction and then there are those who choose to adjust gearing ratios or tweak the carburation etc but none of these methods would be sufficient for Manolo Cachorro. They simply didn’t go far enough.

Manolo acquired an OSSA Yankee 500 and took it into his workshop in Salamanca where he painstakingly stripped it down, examining and evaluating every piece down to individual nuts and bolts. He then spent more than 3 years redesigning, replacing, improving, and manufacturing virtually everything that he deemed necessary to enhance the performance of the bike that he would rebuild. The exact timeline of each stage of rebuilding is unknown and some aspects would have taken place concurrently, but we can outline the main changes.

Firstly, the engine, as seen below.

Having assessed the crankcases and gearbox, he judged them to be of sufficient quality as to not require anything else to be done, so they were effectively left as they were (and they were probably the only things that were). Next came the crankshaft which, though generally considered adequate, still received uprated high-speed bearings and improved seals and, with this done, he turned his attention to one of the main known weaknesses of the engine, the connecting rods.

In addition to OSSA, Manolo was also a concessionaire for the Swedish brand, Husqvarna and he was well aware of both the quality of the steel used by them and their exacting engineering tolerances. It was hardly surprising that he looked to them for a solution to the problem.

Interestingly, in 2003, the Spanish publication Moto Clásica looked at the work done on the engine by Manolo and made the point that almost a pair of the OSSA connecting rods could be made from the material contained in one Husqvarna one! The connecting rods required hours of work and Manolo created a special jig that allowed him to cut and then reweld the revised versions until he was satisfied. Whilst cutting and welding connecting rods sounds extreme, the quality of his workmanship was such that he undertook this, working to very exacting tolerances and, when completed, the bike campaigned for 3 seasons racing without any connecting rod issues. The “bottom end” was almost complete and, having satisfied himself that he had resolved the connecting rod issues, Manolo chose Mahle pistons, as per the Husqvarna.

The next stage of the engine development within the project was the fundamental change that would improve performance. When considering his engine redesign, he had already decided to abandon air cooling and he had designed a system for water cooled cylinders. This was always a contentious subject with enthusiasts, particularly the traditionalists as with water cooling, you have to lose the normal finned appearance of the cylinder blocks and the result isn’t always the most attractive to look at. The necessary pipework and its associated radiator(s) always seem to irritate purists, but it is undeniable that water cooling is a far more efficient means of cooling an engine, particularly a high revving, two stroke engine destined for competition, as was this one.

Manolo designed an aluminium, water-cooled cylinder block and cylinder head assembly and, fortunately, he had a local friend with a foundry who made moulds for Wellington Boots. Between them they made sand moulds for the casting and Manolo had the engineering skills to operate a milling machine and a lathe and he machined crankcases and cylinders. The embedded, internal cylinder sleeves were manufactured with 6 transfers (more than the original OSSA design) and made to a bore and stroke of 69.5mm x 60mm, giving a capacity of just under 460cc (ironically close to the original capacity proposed by Eduardo Giro but with a different ratio on the bore and stroke).

There were many other issues that still needed resolving including the circulation of the water cooling and for this, Manolo chose and adapted a Yamaha pump to the gearbox output and added a compact Yamaha TZ radiator. The ignitions were replaced using a Bultaco unit on one side and an OSSA unit on the other. The carburettors were changed for a pair of the Dell ‘Orto, 34 mm, magnesium type.

Having virtually finished the engine, Manolo turned his attention to the rolling chassis. Surprisingly, the frame is the standard one supplied by OSSA, but it has been refined and improved. One of the big complaints about the OSSA Yankee 500, particularly of those adapted to track use, was the vibration as it was said that it was as if the bike was trying to destroy itself. Manolo added strength to vital points and added a tie rod to the rear brake assembly and, although he retained the original front forks, he changed the valves and seals to improve the handling. The standard OSSA wheels were replaced with Majestic Alloy wheels with detachable rims, with 300mm Brembo twin discs on the front and a Brembo rear disc.

One of the most time-consuming problems to resolve (and perfect) was the exhaust system. It took hours of painstaking work and adjustments and eventually, Manolo had made 9 complete sets of exhausts (18 pipes in all). He experimented with different diameters, different lengths, different cones (and counter-cones) until he was finally satisfied. Although Manolo only had a small workshop, he had saved his spare money and invested in one of the first German Schenk eddy current brake test benches in Spain in 1978.

As he modified the exhaust system, he was able to remove much of the guesswork and see the results on the test bench. Eventually, by the time that he was finally satisfied, his bike was delivering an incredible 89 hp at the rear wheel.

After more than 3 years’ work, the Cachorro Motor Racing bike was ready for the track. It was tested by Andrés Pérez Rubio and raced in the Spanish Motociclismo Super Series, ridden by Javier Serrano and Juan Abella.

In its first race, at Lugo, Eduardo Giró himself was there and, on seeing the bike, he spoke to Manolo and said “Manuel, you’re crazy, what a job you’ve done”.

Manolo Cachorro passed away in 2011 but he left behind a memorable mechanical legacy that acts as a testament to his engineering skill, his vision and, above all, his passion for motorcycles.

In the city of his birth, stands the Museo de Historia de la Automation de Salamanca (MHAS), one of the first museums dedicated to vehicles created in Spain. It is fitting that his magnificent Cachorro 460 cm3 racing bike is on prominent display there.